Swamplife

The Everglades is an iconic and complicated landscape. It epitomizes all that we think of as nature at its most uncultivated: a landscape infested with frightening reptiles, botanical excess, swarms of mosquitoes and unforgiving heat. At the same time, it is portrayed as fragile, unique, and requiring restorative interventions – and the focus of one of the most expensive restoration programs ever attempted. Today, all of these contradictory visions of the Everglades have become entangled into a set of practices and politics of nature that breach division of local and global, nature and culture. Yet, still, within this entanglement, the place of people in the Everglades remains highly ambivalent. For the most part, the Everglades humanity has been displaced to roles of externalized agents of change, with most accounts of people in the Everglades focused on conflicts over drainage and resources.

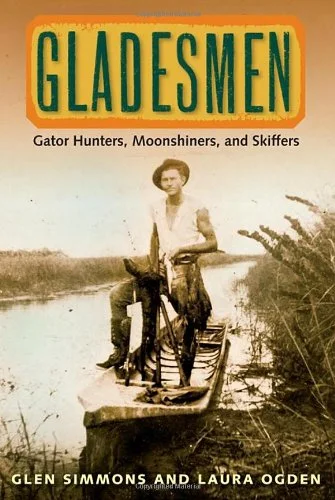

I began my research in the Everglades in the 1990s – when I began an oral history project with a man named Glen Simmons. Glen was sort of an adopted grandfather to me. I spent lots of weekends and holidays at his house, that borders Everglades National Park. I started interviewing Glen interested in his memories of the Everglades and particularly about environmental change in the Everglades. Now what really shocked me – a thing I didn’t know – was that for most of Glen’s life he had been a commercial alligator hunter. The reason I didn’t know this was that he never talked about it. And the reason he never talked about it was because alligator hunting in Florida was illegal and had been for his entire life.

As I interviewed more people, like Glen, I was interested in understanding what the Everglades means to alligator hunters – and how these meanings differ from our more dominant ecological understandings of the Everglades.

Over the years my interest has shifted from understanding this perspective – to understanding the processes by which this history and experience of the landscape became marginalized, illegal, and largely forgotten. I refer to these processes of effacement as the politics of nature.

There are multiple displacements that have simplified the human history of the Everglades – including 10,000 years of indigenous history. My project examines the history and experience of white glades hunters and their families who settled in the everglades backcountry at the midpoint of the 19th century.

My research revolves around a mangrove swamp in the southern Everglades, called the Bill Ashley Jungles. The Bill Ashley Jungles was named for a gang of outlaws who robbed banks, killed policemen, made and sold illegal liquor, during the 1920s. Most notably, the gang evaded capture for years. They taunted police at every turn, and when incarcerated, they repeatedly escaped from jail, prison and several posses. Their successful evasion of the law, at least until their leader was shot down one dark evening on a lonely bridge, was due, in part, to their intimate knowledge of the mangrove swamps. Now, as interesting as their story is – I must admit – I became obsessed with the Ashley Gang because one of the members was a woman named Laura, whom the press dubbed “The Queen of the Everglades”. This coincidence really drives the narrative structure of my book Swamplife. Walter Benjamin compared his method of writing critical history to a sea journey where the ship has been drawn off course by the magnetic north pole. For Benjamin, critical illumination appears as we follow the deviations of history’s main line. As he says, “Discover that North Pole” (1989, 43). The Queen of the Everglades is this project’s north pole –and I return again and again to the mangrove swamps they called home.

Publications and Other Materials

Research Collaborators

The National Science Foundation’s Florida Coastal Everglades (FCE) Long Term Ecological Research Program generously supported much of my Everglades research. More importantly, the LTER program and my colleagues at FCE continue to provide a research community that allows for interdisciplinary thinking and writing to flourish.

Deborah Mitchell is a South Florida artist and Executive Director, AIRIE (Artists in Residence in Everglades). Her Everglades photographs provide an important visual thread in Swamplife.